A new exhibit at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City celebrating 150 years of the great Western Trail is on view through January 5, 2025.

“Imagine wearing wet clothing for six months. You’re dirty and you’re wet, and your clothes never dry out because you’re either crossing a river, or it’s raining, or you sweated through your clothes multiple times,” says Michael R. Grauer, President of the Western Cattle Trail Association. Grauer has thought a lot about the unnamed cowboys who rode along the great Western Trail, which handled more cattle than all the other cattle trails combined and lasted the longest, from 1874 to 1897. It also stretched the farthest, from Mexico to Canada through nine American states — and helped to create ranches all across the West. “The Western Trail had global consequences,” Grauer says. “It’s an incredible economic story.” Yet the Western Trail is much less known than the eastern Chisholm Trail, whose route through populous modern cities with savvy tourism industries has garnered fame and familiarity.

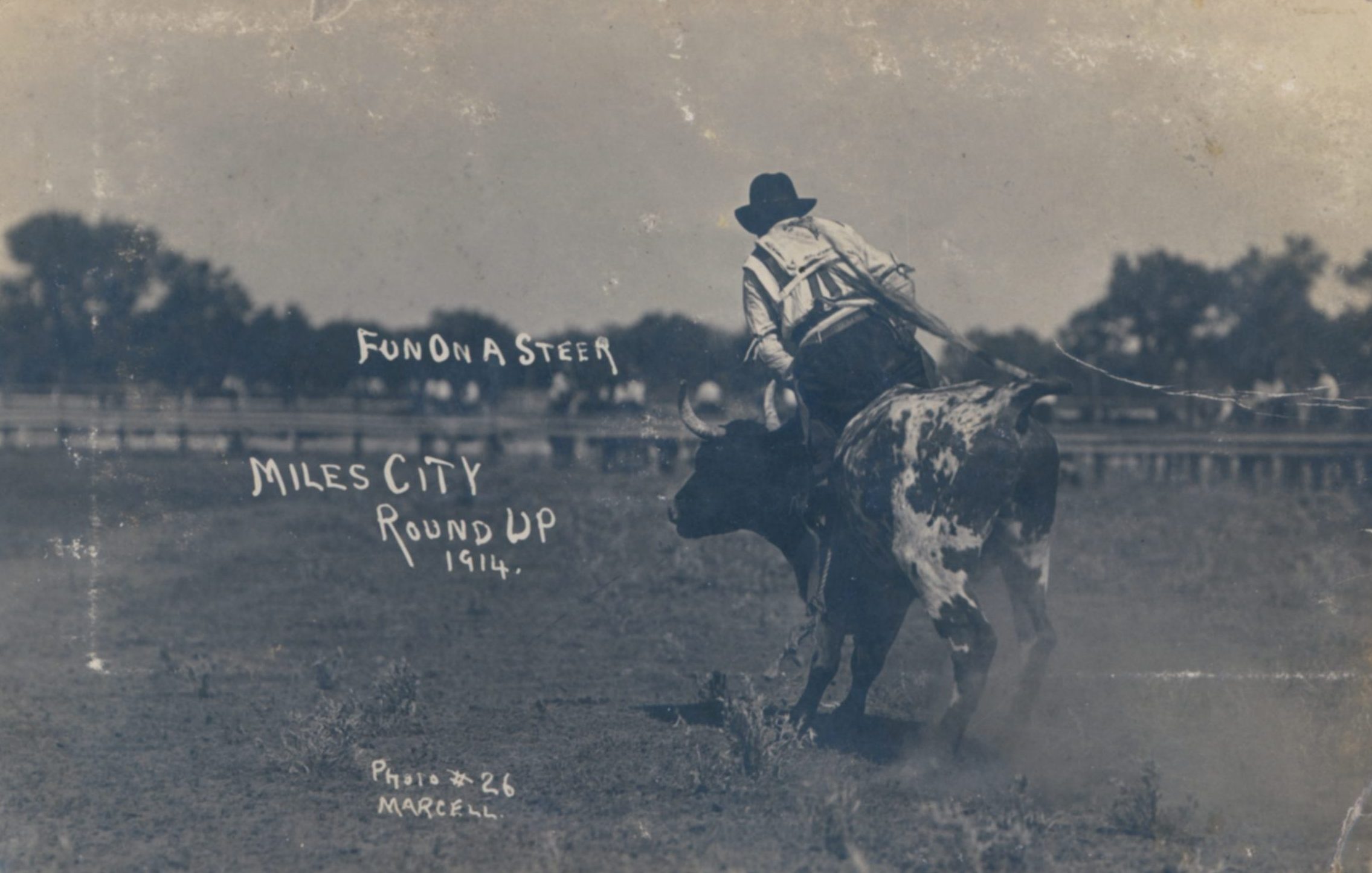

“Fun on a steer” at the Miles City Round-Up, 1914 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Edward F. Marcell, Dickinson Research Center, Howard Tegland Rodeo Postcards Collection, 1911.046.027).

“Fun on a steer” at the Miles City Round-Up, 1914 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Edward F. Marcell, Dickinson Research Center, Howard Tegland Rodeo Postcards Collection, 1911.046.027).

The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City hopes to rectify that with a new exhibition honoring the great Western Trail’s 150th birthday. Showing from September 13, 2024, to January 5, 2025, The Western Trail: The Greatest Cattle Drive of Them All at 150, explores the route’s unique story and stouthearted cowboys. “The drovers who went up the trail are the key to understanding it,” explains Grauer, who is also the museum’s Curator of Cowboy Collections & Western Art and McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture. The exhibit traces the Western Trail’s evolution and cultural impact through historical relics and photography, objects d’art, and artifacts from television and film.

It all starts with John T. Lytle, the San Antonio cattleman who pioneered the great Western Trail in 1874 with 3,500 longhorns. Lytle rode north from his ranch in Medina County, Texas, on a path roughly parallel to the Chisholm Trail and about 125 miles to the west. He traveled straight through western Oklahoma to Dodge City, Kansas, where busy railheads connected to the hungry meat markets in Chicago and St. Louis. But Lytle wasn’t shipping his Texas cattle east, and Dodge City wasn’t his final destination. He continued on to Nebraska’s northwestern corner and delivered his herd to Camp Robinson (now Fort Robinson) and the Red Cloud Agency, one of the new reservations for the Arapaho, Northern Cheyenne, and Oglala Dakota tribes. When the reservations where established, the treaties stipulated the federal government would provide the internees with rations. “Someone had to get the beef cattle to Red Cloud Agency, and Lytle was fortunate enough to secure that contract,” Grauer explains. Lytle’s route caught on quickly, launching multiple feeder trails and splinter routes. Just five years after his initial journey, the Western Trail had supplanted all the others.

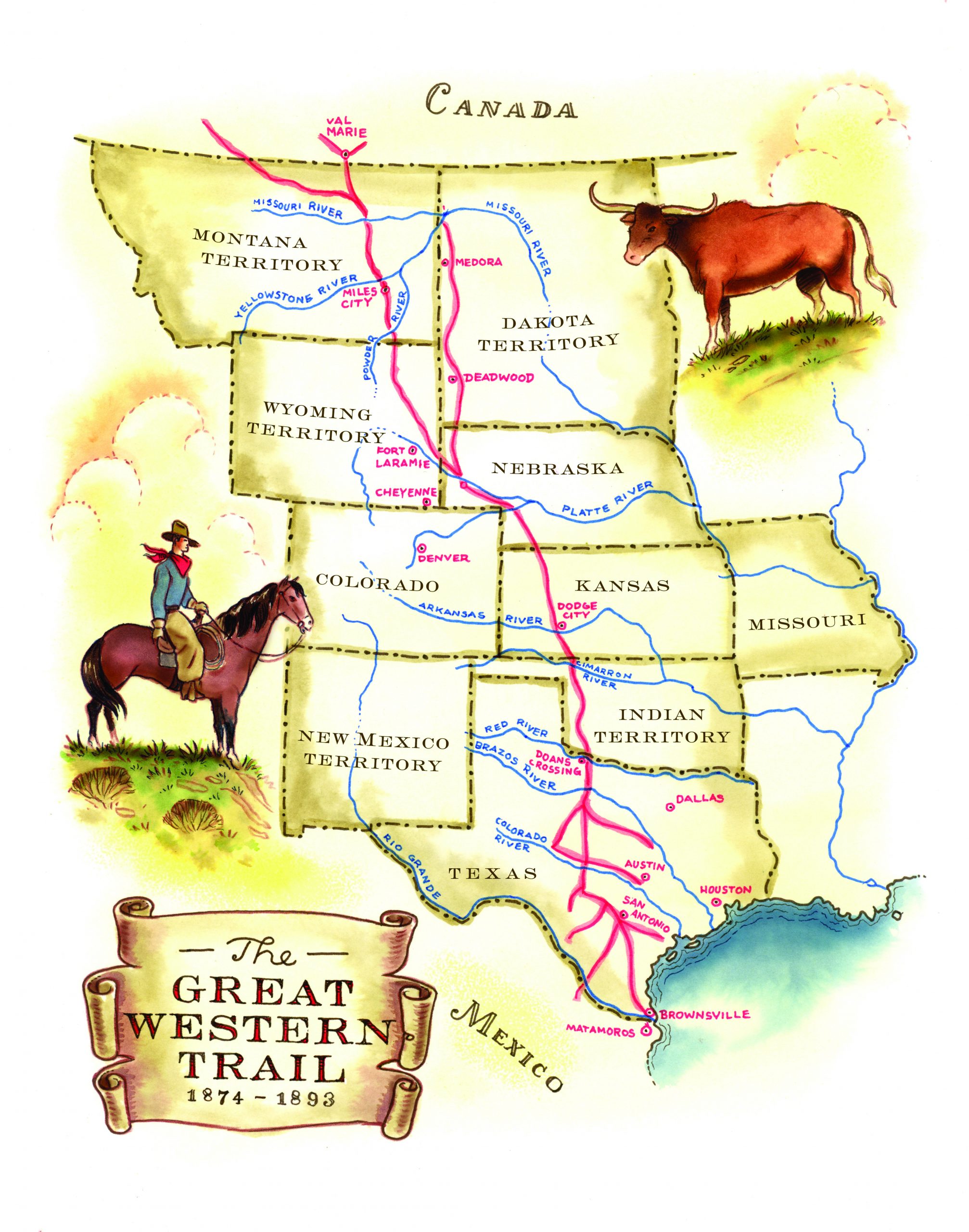

Map of the “Great” Western Trail (PHOTOGRAPHY: Ross MacDonald)

Map of the “Great” Western Trail (PHOTOGRAPHY: Ross MacDonald)

Catching Fire

Part of the trail’s quick rise to dominance was due to the advancing frontier and the arrival of farmers with fences and fields. They didn’t take too kindly to Texas longhorns or the ticks they carried that spread deadly Texas fever to local cattle. Homesteaders in eastern Kansas began imposing quarantines to keep the longhorns out before the Civil War. As the quarantines spread westward with the line of settlement, drovers had to find a better route. Lytle’s trail provided a solution.

His route grew even more attractive in 1875 after the Red River War, a U.S. Army campaign that brought an end to the free-roaming Indian tribes on the southern Great Plains. By 1880, the buffalo were gone. The Kiowa, Arapaho, Comanche, and Southern Cheyenne watched their traditional ways of life disappear as they were forced from their homelands onto reservations. But for drovers, the Western Trail became a safer option. “Depredations were a thing of the past for the most part,” Grauer says. “There were renegade attacks, but they were very, very rare.”

Compressed Beef — Cattle Shipping Scene, Montana, 1904 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Benjamin L. Singley (1864 – 1938), Keystone View Company, Photographic Study Collection, Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 2003.136).

Compressed Beef — Cattle Shipping Scene, Montana, 1904 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Benjamin L. Singley (1864 – 1938), Keystone View Company, Photographic Study Collection, Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 2003.136).

In 1885, Kansas closed its entire border to Texas longhorns and the Western Trail swung farther west into Colorado to connect with the vast, open grasslands of Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakota Territories. Popular culture usually depicts cattle drives ending at Kansas railheads like Abilene or Dodge City. But that’s just part of the story. While plenty of cattle on the Western Trail were shipped east on trains, the majority proceeded to the northern plains where they stocked new ranches as part of the “feeder” system.

Farmers in the Midwest had long bought so-called feeder cattle and fattened them or “finished” them with corn before selling the fattier, tastier beef at a profit. On the Western Trail, the feeder system took advantage of the open ranges in the north to fatten and finish the cattle on grass. “Longhorns aren’t terribly tasty, so there was an attempt to improve the breed,” Grauer says. America’s diet had shifted from pork and chicken toward beef after the Civil War, and now the country’s palate was growing more refined. Grass-finished beef catered to this change and commanded high prices launching a beef bonanza on the northern plains. “Everyone was trying to get involved in this beef opportunity, to get rich quick before the ranges were fenced off.” They all went up the Western Trail.

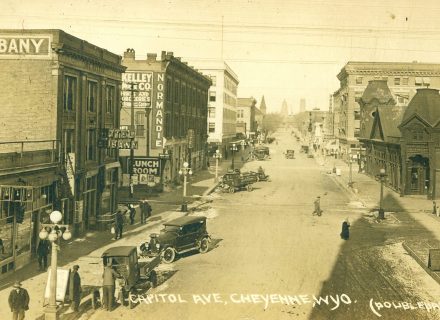

Capital Avenue, Cheyenne, Wyoming, ca. 1920 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Ralph R. Doubleday, Dickinson Research Center, Photographic Study Collection, RC2007.050.1).

Capital Avenue, Cheyenne, Wyoming, ca. 1920 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Ralph R. Doubleday, Dickinson Research Center, Photographic Study Collection, RC2007.050.1).

Journey Up The Trail

The museum exhibit follows this far-flung route while highlighting key places and figures like trail driver John T. Lytle. Visitors can see some of the trailblazer’s possessions before learning about San Antonio’s Menger Hotel and Buckhorn Saloon, two renowned hangouts near the start of the trail. After exploring Fort Griffith, Texas, the exhibit looks at Doan’s Crossing, a trading post and the drovers’ last stop before entering Indian Territory across the Red River (now Oklahoma). Doan was a conscientious shopkeeper who recorded every trail boss’s name and the number of cattle passing through — an incredible 301,000 in 1881.

Herds skirted the western edge of the Comanche-Kiowa-Apache Reservation before heading toward Fort Supply and the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation. Drovers gave the tribes a handful of cattle as a “toll” in exchange for safe passage and grazing rights. Some Native Americans accumulated sizable herds and became successful cattlemen themselves, such as the famous Comanche chief Quanah Parker. One of the museum’s standout pieces is a bison hide that depicts the camp at Fort Supply, painted by a Kiowa man named Woody Big Bow.

“A mess scene” from a roundup in Dakota territory, 1887 (PHOTOGRAPHY: John C. H. Grabill, Dickinson Research Center, Photographic Study Collection, 2005.278.2).

“A mess scene” from a roundup in Dakota territory, 1887 (PHOTOGRAPHY: John C. H. Grabill, Dickinson Research Center, Photographic Study Collection, 2005.278.2).

Hollywood artifacts also breathe life into the exhibit, including a costume worn by Dodge City’s Marshal Dillon (actor James Arness) in Gunsmoke and a prop from the Lonesome Dove miniseries (set on the Western Trail) from a scene with Tommy Lee Jones. South Dakota is represented by Ian McShane’s ensemble from the HBO production Deadwood and John Wayne’s hat from the movie The Cowboys, which references the city of Belle Fourche. You’ll also see a Colt revolver carried by John B. Kendrick, Texas cattleman-turned-Wyoming governor and U.S. Senator, plus weapons and a uniform from Canada’s North-West Mounted Police.

Danger & Determination

But the real Western Trail was no Hollywood movie — the cattle drive was hardcore. Cowboys confronted death-threatening hazards on a regular basis, from ground-shaking stampedes to terrifying hail and lightning storms. “There literally were no trees from northern Mexico all the way to Canada,” Grauer says. “On the back of a horse, you’re the tallest thing around during a lightning storm. There’s nowhere to go. There’s no overpass to pull your horse under during a hailstorm.” Flash floods were the biggest menace; cowboys were constantly crossing perilous rivers. “Drowning happened all the time, not just with animals but with men. We have graves of these drovers all across the West, and they’re virtually all unmarked.”

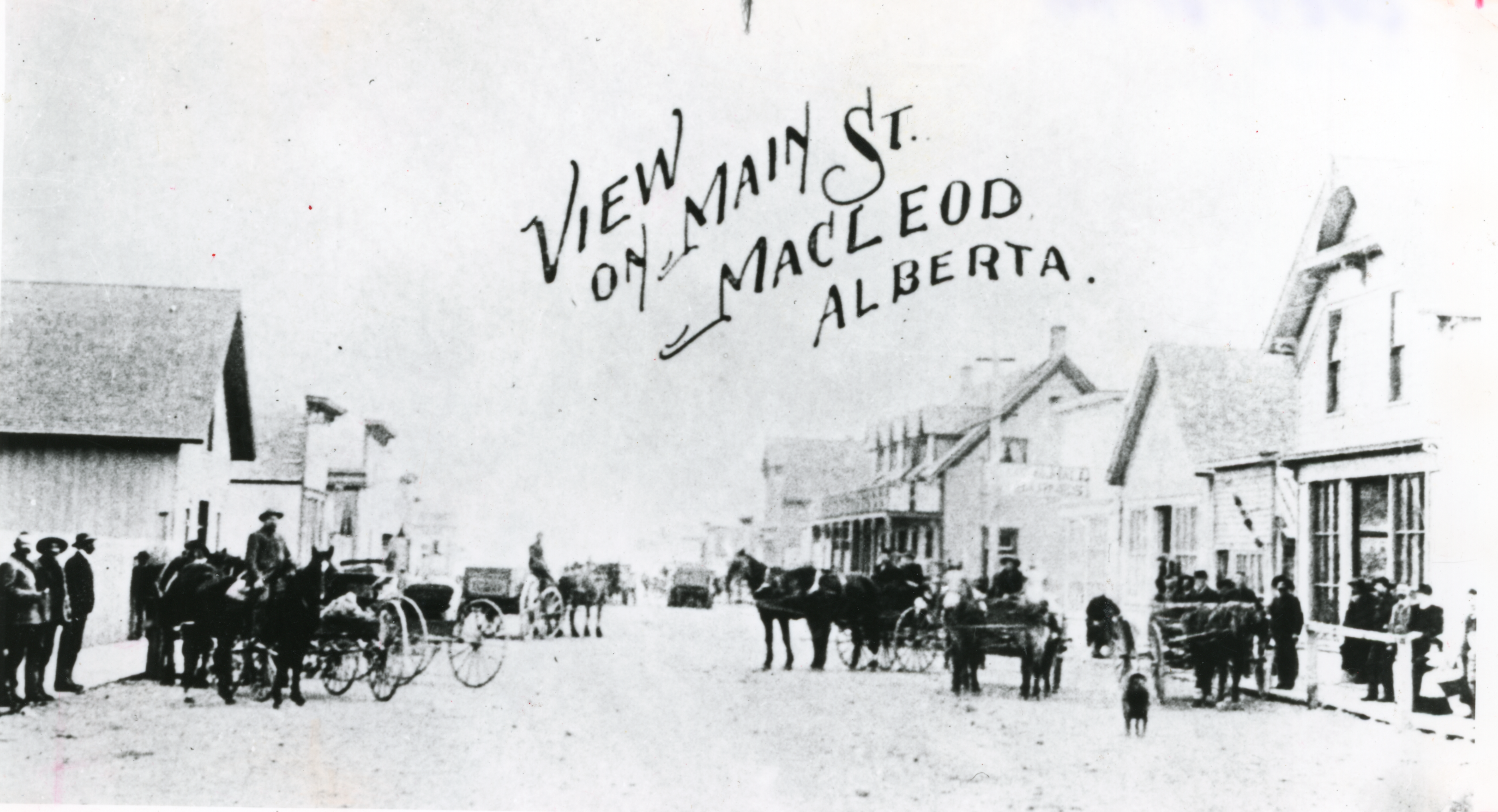

View of Main St., Macleod, Alberta, ca. 1860 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Dickinson Research Center, John Santangelo Collection, 1994.010.0854).

View of Main St., Macleod, Alberta, ca. 1860 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Dickinson Research Center, John Santangelo Collection, 1994.010.0854).

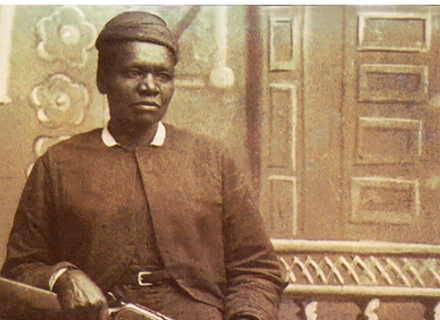

Cowboys came from all walks of life and were simply cut from stronger stuff, whether they were ex-Civil War soldiers or teenage boys or the formerly enslaved. About 25 percent were Native Americans, African Americans, and Hispanic vaqueros. Even some women traversed the Western Trail, like Molly Goodnight, who rode from Texas to Dodge City at least three times. Most cowboys were young, between 15 and 25 years old. But despite their youth, they shared a sense of honor and resolve that inspires us still today.

“It was a point of pride with those drovers that if you signed on, you stood by your word and you finished the job,” Grauer says. Not every cowboy completed the trail, but the bulk of them did — because they said they would. “I hope visitors take away how far it went, how hard it was, and the intestinal fortitude and the perseverance that it took to complete this work. Because it was so damn hard, and it was so dangerous.”

Rear View, Albert’s Saloon, San Antonio, Texas, February 1921 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Gerald J. McIntosh Papers, Dickinson Research Center, H.116.015.07).

Rear View, Albert’s Saloon, San Antonio, Texas, February 1921 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Gerald J. McIntosh Papers, Dickinson Research Center, H.116.015.07).

End Of An Era, Beginning Of A Legend

The entire trail system connected nine American states (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana) as well as northern Mexico and western Canada — but frontier settlement, barbed wire, and tastier breeds were inexorably bringing the cattle drives to an end. The last major drive reached Montana from Texas’ XIT Ranch in 1897, then the cattle trail was closed. All in all, 6 to 8 million cattle and 1 million horses had traveled up the Western Trail.

The golden age of the cowboy may be over, but it’s left an indelible mark. “The Western Trail built America,” Grauer says. “This great country was built on beef and bread; it wasn’t built on broccoli. Cowboys and farmers built this country.”

Old Time Trail Drivers Assn., San Antonio, Texas, March 1915 (PHOTOGRAPHY: C. L. Steinle (1875 – 1954) Leo Noble Photographs, Dickinson Research Center, H.030.1).

Old Time Trail Drivers Assn., San Antonio, Texas, March 1915 (PHOTOGRAPHY: C. L. Steinle (1875 – 1954) Leo Noble Photographs, Dickinson Research Center, H.030.1).

The enduring appeal of the cowboy touches something much deeper in the human spirit. “There’s no more recognizable nor admired symbol worldwide than an American cowboy, because they stand for something. A human on horseback attains mythical status as a symbol of freedom and liberty,” says Grauer, whose mission is to make sure that we never forget the cowboys of the Western Trail. “It’s the anonymous drover that inspires me, the ones whose names we don’t know and never will know, who are buried in those unmarked graves all across the West.”

Between the silent graves and the towering mythos of the cowboy, there lies a Great Western cattle trail — and an exhibit that tells the story of those who can no longer speak for themselves

If You Go

What: The Western Trail: The Greatest Cattle Drive of them All at 150

When: September 13, 2024, to January 5, 2025

Where: National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

1700 NE 63rd St,

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

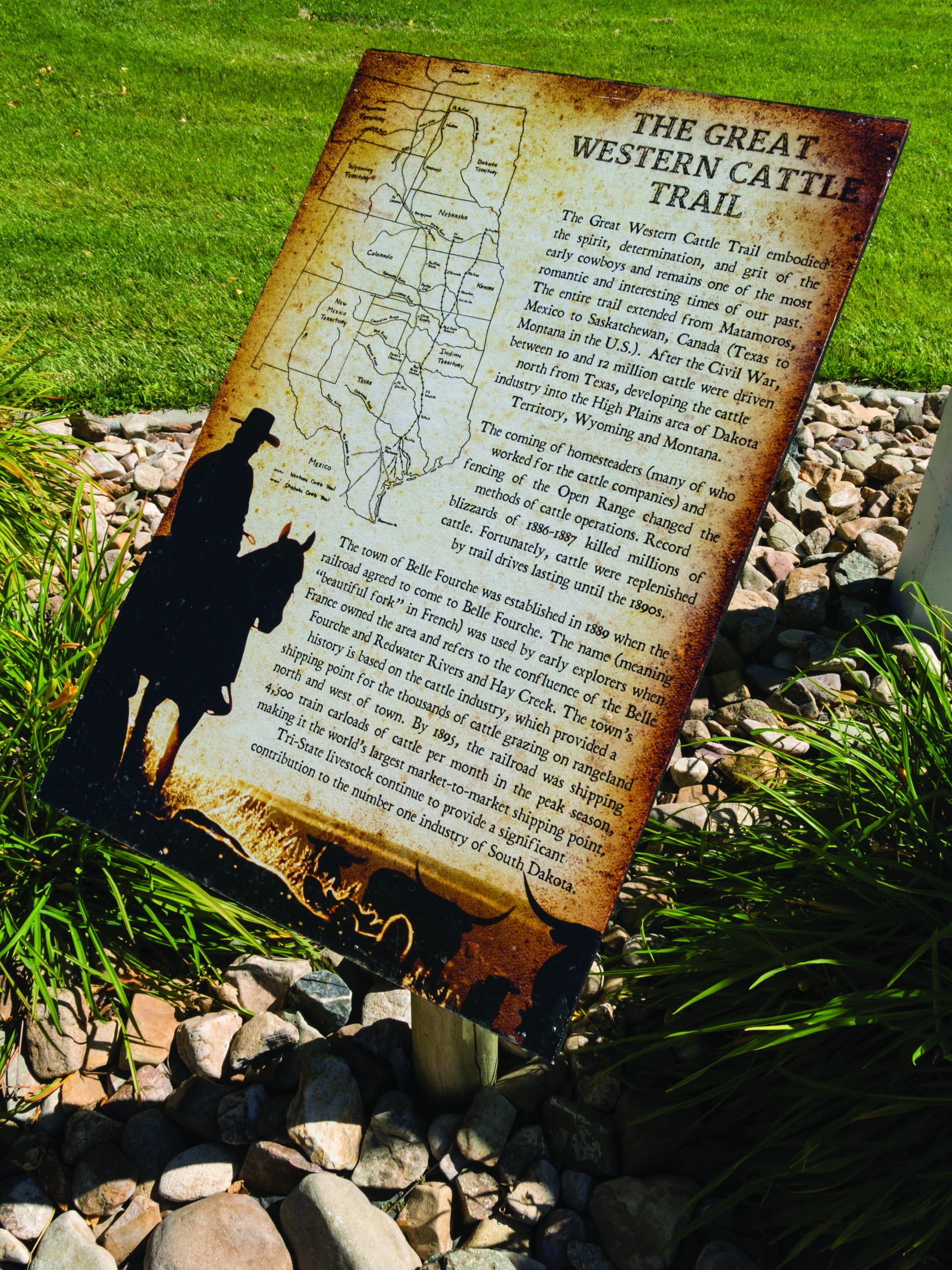

Today, there are still places to stop and learn about The Western Trail including in the Historic District of Belle Fourche, South Dakota (PHOTOGRAPHY: Patti McConville/Alamy Stock Photo).

Today, there are still places to stop and learn about The Western Trail including in the Historic District of Belle Fourche, South Dakota (PHOTOGRAPHY: Patti McConville/Alamy Stock Photo).

For Further Reading: The Western Cattle Trail 1874 – 1897, Its Rise, Collapse, and Revival by Gary & Margaret Kraisinger

Learn where to hop in the trail for your own excursion here.

From our November/December 2024 issue.