A new exhibition at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art explores how Native American and non-Native art created between 1785 and 1922 coexists and celebrates the diverse West.

Amid stunning architecture and 120 acres of Ozark nature, Knowing the West opens this fall at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. A major traveling exhibition, it celebrates the American West as inclusive, complex, and reflective of the diverse peoples who contributed to the art and life of the West.

Co-curated by Mindy Besaw, Crystal Bridges’ curator of American Art, and Jami Powell (Osage Nation), curator of Indigenous art at Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, the exhibition presents more than 120 artworks, including textiles, baskets, paintings, pottery, sculpture, beadwork, saddles, and prints by Native American and non-Native American artists. On view September 14, 2024, through January 27, 2025, the show will travel to two additional venues and will be accompanied by a fully illustrated book published by Rizzoli Electa.

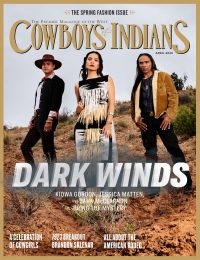

“Art of the West is so often presented in simplified and binary terms — such as ‘cowboys and Indians’ — which does little to embrace the multiplicity of more than 550 Native nations in present-day United States, let alone artworks made by European-American women, Black artists, and New Mexican Hispanic artists,” Besaw says.

“In addition to highlighting the multiplicity of Indigenous experiences in ‘the West,’ we have paid significant attention to sharing the authority and power of women makers,” Powell adds. “Most of the Native American artworks in the exhibition were made by women, who we honor for their artistry, skills, and cultural knowledge.”

As co-curators, Besaw and Powell are hopeful that the exhibition, taken as a whole, demonstrates that the “canon” is not the best benchmark for American art. “By exhibiting artworks in a variety of media and by including a range of makers, this exhibition aims to question and flatten hierarchies in American art,” Besaw says. “In fact, this approach can serve as a model for how to rethink and re-present American art broadly.”

C&I asked Besaw and Powell for an exclusive sneak peek at a dozen works that exemplify the show and the creative, coexisting spirit of the American West.

Joseph No Two Horns or He Nupa Wanica (Hunkpapa Lakota, Teton Sioux, 1852 – 1942); Winter Count; Ca. 1922; Depicting the years 1785 – 1922; Ink, watercolors, and crayon on muslin; 93 x 36 inches; Gift of Jo Anderson, Omaha, Nebraska (PHOTOGRAPHY: Jeffrey Wells).

Joseph No Two Horns or He Nupa Wanica (Hunkpapa Lakota, Teton Sioux, 1852 – 1942); Winter Count; Ca. 1922; Depicting the years 1785 – 1922; Ink, watercolors, and crayon on muslin; 93 x 36 inches; Gift of Jo Anderson, Omaha, Nebraska (PHOTOGRAPHY: Jeffrey Wells).

Lakota peoples are some of the longest residents of the West, recording time and memorable events from their communities on a single hide or muslin. This winter count by Joseph No Two Horns depicts more than 130 years of history with each year represented in a single image. As the first object visitors will see, the No Two Horns drawings establish the temporal scope for the exhibition: artwork made between 1785 and 1922, the years illustrated in the winter count. The winter count is surprisingly large, retains color, appears unaltered, and has rarely been seen in the last century. More significantly in this context, it sets the tone for the exhibition and presents time and history as community-driven, interdependent, and multifaceted.

Louisa Keyser or Dat-So-La-Lee (Washoe, 1829 – 1925); Degikup, 1917 – 1918; Willow, redbud, and bracken fern root; 12¼ x 16⅜ inches (diameter); Philbrook Museum of Art; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Gift of Clark Field; 1942.14.1909 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Philbrook Museum of Art).

Louisa Keyser or Dat-So-La-Lee (Washoe, 1829 – 1925); Degikup, 1917 – 1918; Willow, redbud, and bracken fern root; 12¼ x 16⅜ inches (diameter); Philbrook Museum of Art; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Gift of Clark Field; 1942.14.1909 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Philbrook Museum of Art).

Louisa Keyser is credited with revolutionizing Washoe coiled basketry, and this is one of the finest known examples of her work. Keyser transformed the shape and design of the degikup, or utilitarian basket, making sculptured baskets with coiled willow and bracket fern (black) and redbud (red) for the designs. Washoe peoples live in the eastern Sierra Nevada mountain range, where they have lived for at least the last 6,000 years. In the exhibition, Keyser’s Degikup and baskets by Elizabeth Hickox (Karuk/Wiyot) will be featured in dialogue with Albert Bierstadt’s Sierra Nevada Morning, insisting on not only the presence of Indigenous people in the landscape, but their deep knowledge and engagement with these ancestral homelands.

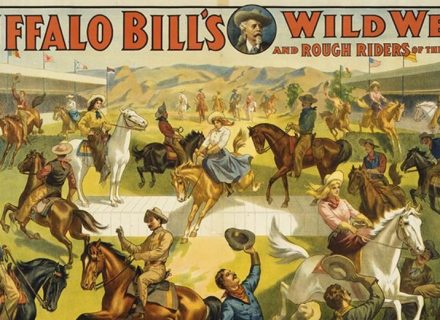

Grafton Tyler Brown (American, 1841 – 1918); A Yellowstone Geyser; 1887; Oil on canvas; 28 x 11 inches; Museum of Fine Arts; Boston, Massachusetts; Emily L. Ainsley Fund and the Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection; 2009.4329 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Grafton Tyler Brown (American, 1841 – 1918); A Yellowstone Geyser; 1887; Oil on canvas; 28 x 11 inches; Museum of Fine Arts; Boston, Massachusetts; Emily L. Ainsley Fund and the Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection; 2009.4329 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Among the few Black artists working in the American West, Grafton Tyler Brown was born free in Pennsylvania in 1841. Brown’s work would likely have been the first encounter many Americans had with images of an otherwise-unfamiliar terrain, given that his career included the production of lithographs depicting the young, alluring state of California. In this sense, Brown occupied a very peculiar position, contributing to the draw of westward migration for Black Americans who, like the artist, were seeking solace during the era of Reconstruction, even as the accessibility of this territory depended on the forced removal of its Indigenous people.

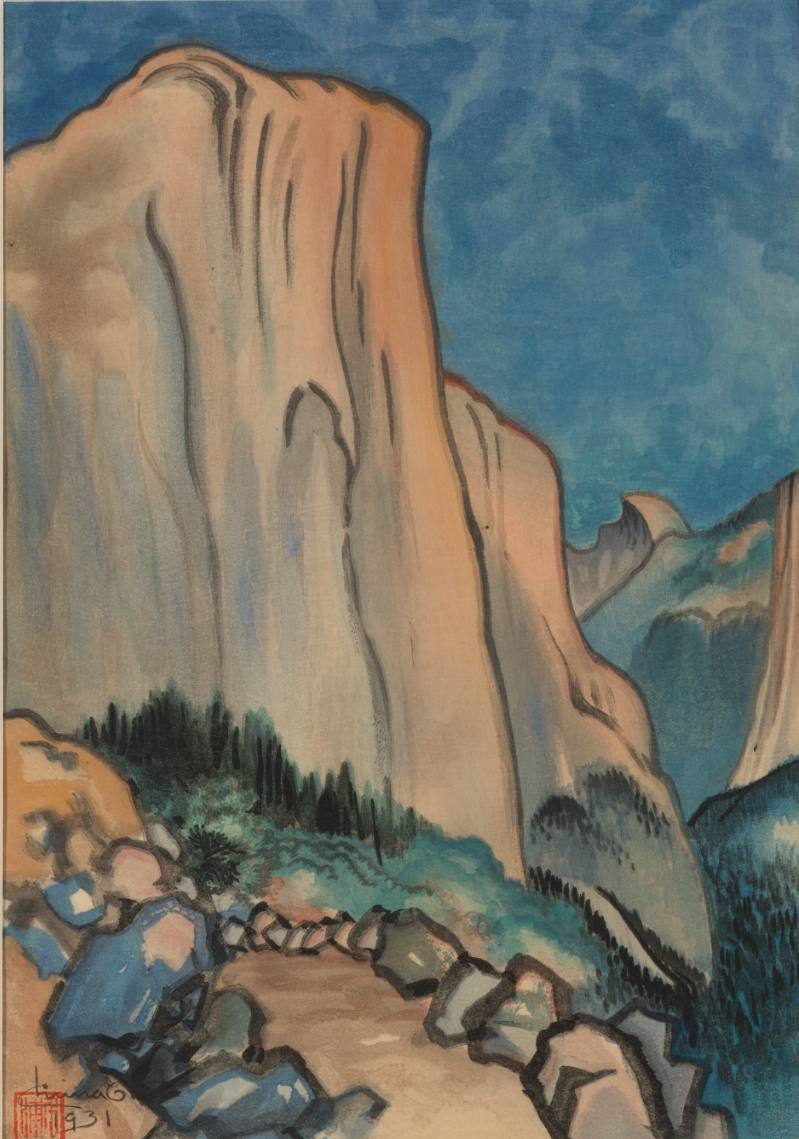

Chiura Obata (American, Born in Japan, 1885 – 1975); El Capitan; From World Landscape Series “America;” 1931; Color woodcut on paper; 15⅝ x 11 inches; Smithsonian American Art Museum; Washington, D.C.; Gift of the Obata Family; 2000.76.24 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © Courtesy of the Chiura Obata Estate).

Chiura Obata (American, Born in Japan, 1885 – 1975); El Capitan; From World Landscape Series “America;” 1931; Color woodcut on paper; 15⅝ x 11 inches; Smithsonian American Art Museum; Washington, D.C.; Gift of the Obata Family; 2000.76.24 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © Courtesy of the Chiura Obata Estate).

Chiura Obata visited Yosemite National Park and the Sierra Nevada mountain range in 1927, making over 100 drawings based on his experience. Obata collaborated with Takamizawa, a Japanese printing company, to make the woodblock prints based on his watercolors. The prints in his resulting portfolio titled the World Landscape Series are astounding for their subtlety and the way the artist and printmakers capture the soft atmospheric brushwork of the watercolors that served as their inspiration. Obata emigrated to the United States from Japan in 1903, and while his artistic and professional career were unequivocally shaped by California, his watercolors and prints carry traces of his Japanese artistic training, reflecting a complex and transnational perspective on the landscape of the West.

Dorothy Brett (American, Born in England, 1883 – 1977); Desert Indian; 1932/1937; Oil on canvas; 40 x 40 inches; Tia Collection; Santa Fe, New Mexico (PHOTOGRAPHY: James Hart Photography).

Dorothy Brett (American, Born in England, 1883 – 1977); Desert Indian; 1932/1937; Oil on canvas; 40 x 40 inches; Tia Collection; Santa Fe, New Mexico (PHOTOGRAPHY: James Hart Photography).

Dorothy Brett first visited Taos in 1924 from her home in London. Although meant to be a short visit, she never left New Mexico and eventually became a U.S. citizen in 1938. Her large-scale painting of a Pueblo person on horseback counters the hypermasculine images of Native warriors typically depicted in Western paintings. The subject is likely based on Tony Luhan (Taos Pueblo), husband of socialite and arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan. The ambiguity of the subject’s gender and monumental view of horse and rider differentiate this painting from more stereotypical depictions.

Artist Once Known (Mexican); Mexican Caballero Saddle; 1820 – 1850; Wood, rawhide, leather, glove leather, chamois, fabric, silver, and cotton thread; 21 x 19 x 21 inches; National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 2018.20.

Artist Once Known (Mexican); Mexican Caballero Saddle; 1820 – 1850; Wood, rawhide, leather, glove leather, chamois, fabric, silver, and cotton thread; 21 x 19 x 21 inches; National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 2018.20.

This remarkable and rare early Mexican saddle made in Alta California features an embroidered suede seat, silver horn cap and rim, and a crupper for the horse’s tail. The saddle was likely made for a hacendado or ranchero on the northern Mexican frontier. This saddle will be installed alongside an early vaquero saddle made of wood and leather, a Crow women’s saddle with a tall horn and back, a Diné (Navajo) saddle embellished with brass tacks, and an ornately beaded Lakota Western-style saddle. The visual variety displayed in the single form of the saddle conveys the diverse artists and cultures coexisting and influencing one another across nations and borders in the West.

Artist Once Known (Nimiipuu, Nez Perce); Saddle Blanket; Ca. 1885; Wool, glass beads, Chinese coins; 40 x 48 inches (sight); National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 1983.06.12.

Artist Once Known (Nimiipuu, Nez Perce); Saddle Blanket; Ca. 1885; Wool, glass beads, Chinese coins; 40 x 48 inches (sight); National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 1983.06.12.

This elaborately decorated saddle blanket reflects innovative use of materials acquired through intercultural exchange and trade. By the 1860s, wool blankets and glass beads had long been significant trade goods between European settlers and Native people across the continent, but the Chinese coins sewn to the edges of the blanket are unique. These coins were no longer used as currency but made their way to North America as ballast in the hulls of ships bringing spices and other imports from the Far East to the American West. The Nimiipuu artist used the coins as both a visual and audible embellishment on the blanket, which would make a jingling sound as the coins struck one another when the horse moved. The coins also point to the influx of Chinese immigrants to the West Coast throughout the 19th century. Many worked in gold mines, agriculture, and factories, especially in the garment industry, but others took on difficult and dangerous jobs in railroad construction.

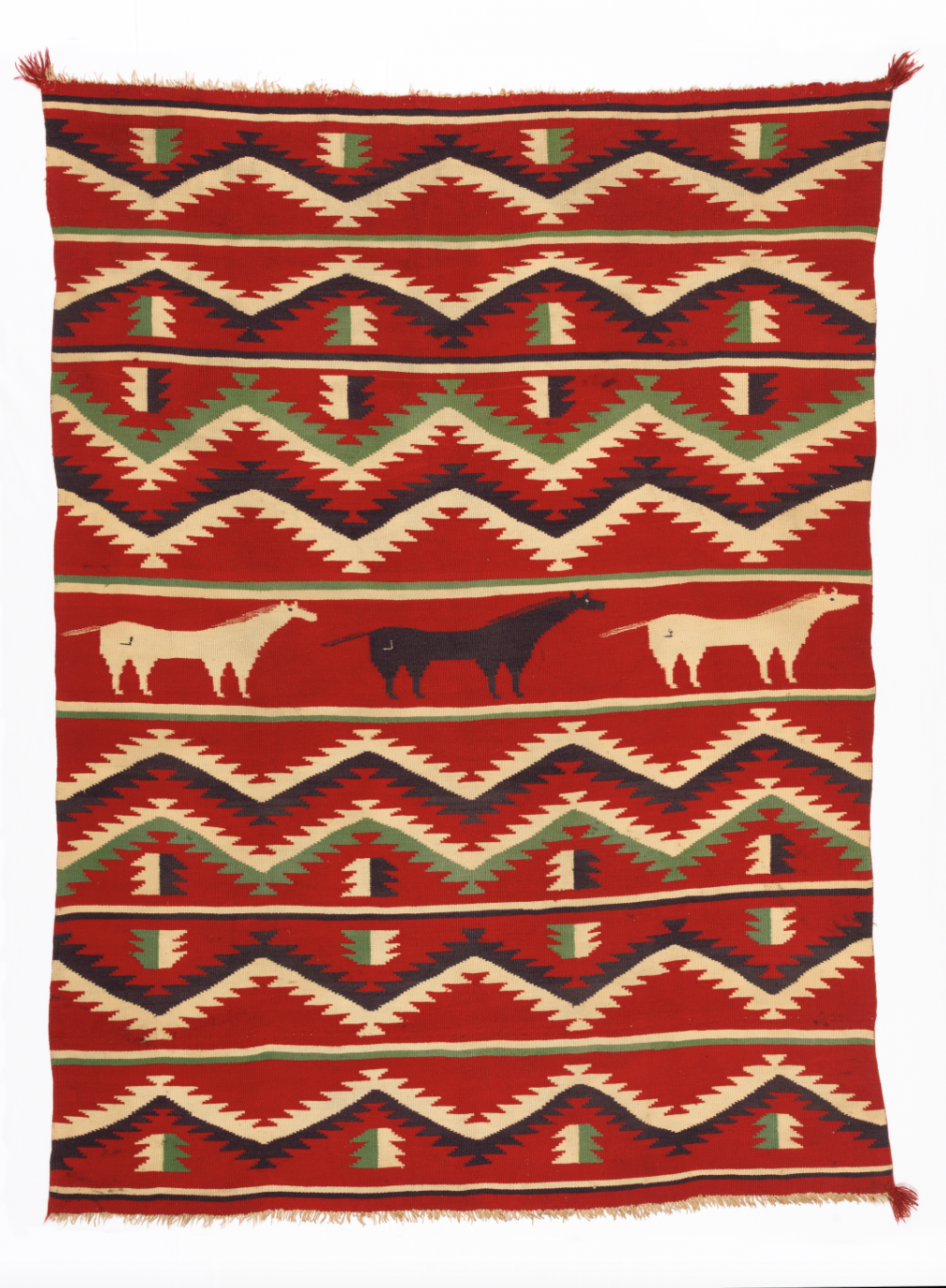

Miranda (Diné [Navajo], Active 19th century); Serape; 1892; Commercial wool yarn and cotton string; 88⅗ x 66⁹⁄₁₀ inches; Denver Museum of Nature & Science; AC.172A.

Miranda (Diné [Navajo], Active 19th century); Serape; 1892; Commercial wool yarn and cotton string; 88⅗ x 66⁹⁄₁₀ inches; Denver Museum of Nature & Science; AC.172A.

When possible, we prioritized artworks with identified makers for the exhibition. In some cases, we know very little about the artist, such as the Diné (Navajo) weaver Miranda, who made this striking Germantown rug near Farmington, New Mexico, around 1892. Named for the Philadelphia suburb where the brightly colored yarns used to make these intricately woven pieces were manufactured, Germantown rugs exemplify the impact of trade and material entanglements on Diné design. According to the collection documents, the Women’s Committee of San Juan County commissioned this weaving for exhibition at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It is possible that “Miranda” was a name given to her by someone from the Women’s Committee and that her history, along with her real name, is lost to the archives.

Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1887 – 1980) and Julian Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1879 – 1943); Polychrome Jar; 1926; Clay and paint; 15½ x 19 inches (diameter); Indian Arts Research Center; Santa Fe, New Mexico; IAF.166 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Addison Doty, Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research).

Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1887 – 1980) and Julian Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1879 – 1943); Polychrome Jar; 1926; Clay and paint; 15½ x 19 inches (diameter); Indian Arts Research Center; Santa Fe, New Mexico; IAF.166 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Addison Doty, Courtesy of the School for Advanced Research).

Maria Martinez and her artistic collaborator husband, Julian Martinez, received widespread recognition during their lifetimes, attracting buyers to San Ildefonso to purchase their pottery. While the Martinezes are most well-known for their black-on-black pottery—a practice which they revitalized through material and archaeological research—this polychrome jar complicates the narrative often told about this famous artistic couple. As with all of their works, Maria would have formed, shaped, and polished this jar while Julian was responsible for painting the surface with the cream-colored slips and black and red paint.

Artist Once Known (Osage); Wedding Outfit; Ca. 1900; Wool, glass beads, and leather; Dress: 45 x 28 inches; Hat: 13½ x 9¼ inches; National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Museum purchase with funds provided by Carol Dickinson, 2008.08A.

Artist Once Known (Osage); Wedding Outfit; Ca. 1900; Wool, glass beads, and leather; Dress: 45 x 28 inches; Hat: 13½ x 9¼ inches; National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Museum purchase with funds provided by Carol Dickinson, 2008.08A.

Clothing and regalia give a broader picture of the rich diversity of people in the West and their complex interactions. Around 1900, Osage women began appropriating and repurposing military jackets and top hats as bridal attire. The coats, originally given to Osage leaders as gifts from the U.S. government, were status symbols associated with tribal leaders. As the popularity of their use in weddings grew and when U.S. military coats became rare, Osage women tailored coats to look like the military garments, adding ribbon and embroidery, and embellishing accompanying silk top hats with brightly colored feathers. Osage wedding attire is a striking representation of cultural entanglements, adaptation, and innovation within a changing West. It is also one of many examples of Native American artworks in the exhibition made by women honored for their artistry, skills, and cultural knowledge.

Nellie Two Bear Gates (Iháƞktȟuƞwaƞna Dakhóta, Standing Rock Reservation, 1854 – 1935); Suitcase; 1880 – 1910; Bead, hide, metal, oilcloth, and thread; 12½ x 17¹¹⁄₁₆ x 10¼ inches; Minneapolis Institute of Arts; The Robert J. Ulrich Works of Art Purchase Fund; 2010.19 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Minneapolis Institute of Art).

Nellie Two Bear Gates (Iháƞktȟuƞwaƞna Dakhóta, Standing Rock Reservation, 1854 – 1935); Suitcase; 1880 – 1910; Bead, hide, metal, oilcloth, and thread; 12½ x 17¹¹⁄₁₆ x 10¼ inches; Minneapolis Institute of Arts; The Robert J. Ulrich Works of Art Purchase Fund; 2010.19 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Minneapolis Institute of Art).

The details and materials that Nellie Two Bear Gates used to make this artwork reflect multiplicities of influences and exchange — from the glass beads made abroad to the Euro-American suitcase or doctor’s bag form. This artwork reflects adaptation and resilience, particularly because it was made while the artist was incarcerated on a reservation. Two Bear Gates includes abstract shapes along the edges relating to generations of Lakota beadwork and quillwork as well as scenes of reservation life, including riders roping cattle, on each side. Her beadwork is a continuation and persistence of Dakota life amid the changing and challenging circumstances of the late-19th and early-20th centuries in the West.

Albert Bierstadt (American, Born in Germany, 1830 – 1902); Sierra Nevada Morning; 1870; Oil on canvas; 55¼ x 85½ inches; Gilcrease Museum; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation; 01.2305 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © Gilcrease Museum).

Albert Bierstadt (American, Born in Germany, 1830 – 1902); Sierra Nevada Morning; 1870; Oil on canvas; 55¼ x 85½ inches; Gilcrease Museum; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation; 01.2305 (PHOTOGRAPHY: © Gilcrease Museum).

Albert Bierstadt’s grand landscape painting portrayed California as an unpopulated land rich with opportunity and promise. Bierstadt’s composition is based on his experience visiting and sketching the Sierra Nevada mountain range in 1863, although he painted the large-scale canvas several years later in his Tenth Street Studio in New York. Throughout the exhibition, deeper explorations into U.S. settler intentions and Native American histories complicate this seemingly larger-than-life vista and other well-known examples of Euro-American art.

Knowing the West will be on view September 14, 2024 – January 27, 2025, at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas; March 26 – August 31, 2025, at Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Jacksonville, Florida; and May 2, 2026 – August 9, 2026, at North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, North Carolina. The Rizzoli book of the same title will be released September 10.

From our August/September 2024 issue.