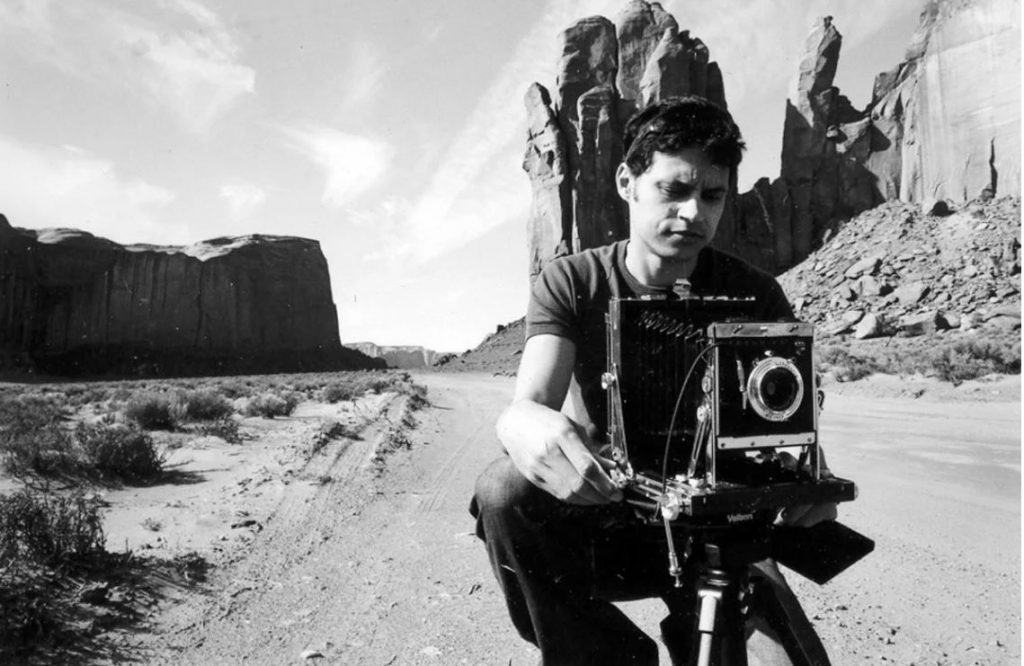

Writer-Director Ivan Sen follows a cop on the trail of a long-missing Indigenous woman.

A mysterious stranger arrives in a remote town, with the announced intention of meting out past-due justice. But the locals are reluctant to provide assistance. A few are embittered relatives of the young woman — long missing and presumed dead — who years ago gave up all hope of ever solving the mystery of her disappearance. Other townspeople are downright hostile, suggesting they know much, maybe too much, about why and how the girl vanished. The more the grizzled lawman investigates, the less certain he is of completing his task and providing closure to those who dearly need it. But a man’s got to do what a man’s got to do…

That plot description for Limbo, writer-director Ivan Sen’s exceptionally fine drama now in limited theatrical release, might raise expectations for a conventional Western, perhaps the kind of oater that once provided gainful employment for actor Randolph Scott and director Budd Boetticher. Or if you can envision a flash-forward, you may find yourself imagining a neo-Western in the vein of John Sturges’ Bad Day at Block Rock (1955).

As it turns out, however, Limbo is something else: A relentlessly gripping and shrewdly slow-burning Australian Noir drama about a big-city cop inexplicably assigned to solve the 20-year mystery of a young Indigenous women. Her disappearance was more or less brushed off by local authorities back in the day, and by now even her surviving friends and family hold out little if any hope for a satisfying resolution. Maybe Travis Hurley (played Simon Baker of The Devil Wears Prada, Margin Call, and TV’s The Mentalist), the stranger in town, will be able to uncover clues by looking at the case with fresh eyes. And maybe, while he’s searching, he’ll find himself.

“The more Travis finds out about the family of 20-years-missing girl Charlotte Hayes,” says Sen, an award-winning Aboriginal filmmaker, “the more he is drawn to them and he sees the way they have been treated. Rather than the victims, the police and justice system have made them feel like they are the criminals to be blamed and then ignored.

“Through my personal family situation, and having made films about missing Aboriginal women and girls before, I have gained an insight into the unrelenting trauma this casts on our Indigenous families. The police and the justice system often don’t really investigate or deal properly with such crimes. The thing I wanted to expose in this film is that even though the crime took place 20 years ago, it’s never a cold case for the family. It could have been yesterday for them, they can’t move on.

“Time is almost at a standstill in this huge desert country and I think the cumulative power of the film is in the intimacy we feel for the family, experiencing their pain, as we learn to know them through the investigation carried out by the detective Travis.”

Sen filmed Limbo in the Outback town of Coober Pedy, which he describes as “an incredible location with its own underground world,” surrounded by “a million or so holes dug to mine opals.

“It’s a very harsh, dry, dusty desert environment and the locals have built their houses, churches and hotels underground to escape the oppressive heat. The town is refuge for a diverse population of outcasts following their opal dream. Coober Pedy is also a tourist town, and yet just beyond its borders traditional Aboriginal communities still live in their culture and language. These elements interplay with my approach to the film, itself influenced by classic 1960s and ‘70’s Noir. Not to mention it’s in black and white.”

Ivan Sen recently spoke with me from his home Down Under to discuss Limbo. Here are some highlights from our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity.

Cowboys & Indians: I’ve got to ask what came first — writing the script or finding this location?

Ivan Sen: Location. It’s such an extraordinary place, and you can’t help but to be inspired by what you see and what you feel around you in that location. And that’s generally how I work. Normally, I find it difficult to write anything unless I go to a real place and I just feel it. I feel the power of that place. It could be a city or it could be the middle of the desert, but there’s an authenticity that I think comes from raising a story from a real live place. And in your characters, as they grow up out of this location.

C&I: The sharp, meticulously composed black-and-white images give Limbo both a look of very hard-edged realism, and a sense of bold stylization. Yes, the story is taking place in a vividly detailed area of the Australian Outback — but at the same time, it almost looks like it takes place on another planet. Travis Hurley, Simon Baker’s character, even has the line, “I came out of the sky” when children ask where he’s from. And you can almost believe him, because now he’s in a place where, hey, they carve hotels out of mountains.

Sen: Yeah, it’s such an otherworldly place, above ground and below ground. You have two million holes in the ground from the opal mines. And you have these incredible houses, hotels, all kinds of things that have been built underground to escape the 50-degree Celsius temperatures it sometimes gets to. And there was a sense of realism, but also formalism within the fabric of the artistic nature of the film. And I think for me, that’s art. It’s when you can present a canvas, but have a sense of reality within that, and can encourage the viewer to think and to ponder and to absorb what they’re looking and listening to.

C&I: Did you always have in mind the idea of doing an investigation into an Indigenous woman’s disappearance?

Sen: It’s something that I have been thinking about for quite a while. And it’s something that’s also very close to my own family. We’ve had a situation where we had a family member go missing, over 20 years ago now, and the local police response in the small town was almost nonexistent in terms of helping the family find her. And the family had to go and basically find her for themselves, and actually found her under a roadway bridge. She had been beaten to death — and there was a very apathetic response even from that point. I guess that is something that’s very important in the inspiration of this story, and I took this idea and merged it into that incredible landscape within the film.

C&I: Of course, this story is going to have a great deal of interest for people here in North America, where there lately has been frequent mention of missing and murdered Indigenous women in documentaries and dramas.

Sen: I think it’s a problem that is faced by many countries around the world that have been colonized. Especially under violent circumstances. And the echoes of that get passed down, and we’re still dealing with those echoes now. And I think it’s a symptom of the divide that is still there between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians.

C&I: One of the many things that impressed me about Limbo is, you really didn’t feel the need to explain why this case had been reopened 20 years later. Like, Travis has been given this assignment because of a protest movement, or something like that. It’s more like, “OK, this guy is there, he’s there to do a job.” Was paring down nonessentials part of your creative approach?

Sen: I think that’s an evolution of me as a filmmaker. As an artist, you’re constantly trying to work on yourself to tell stories in a more honest and pure and uncontrived way. I think that’s the same for a lot of artists. And as you grow and you get older, you become a bit more comfortable in that, and settle into it more and more. And it's not really confidence. It’s just a sense, just a feeling, where you feel content about the work. And you are at the point in your life where you know you don’t need to pump this or that scene full of crazy music for the effect you want. And if anything, it’s killing that effect.

C&I: Travis is a tantalizingly complex character. He’s not a deeply religious person, apparently. And yet, on the other hand, he’s listening to either tapes or radio programming of a religious nature during long drives. He doesn’t have the Beatles or Taylor Swift or anything like that on.

Sen: But he doesn't turn it off.

C&I: True enough. But is it something he turned on in the first place? Is it something that he would always be listening to?

Sen: Yeah, I think so. I think he’s a very delicate character. And his religious or born again connection is layered there as a part of the makeup of him — like in a cake, if you will. He also is an ex-narcotics cop, and he’s had to deal with an addiction as well. His connection with Christianity is just another thing where he’s reaching out for something, because he does have an emptiness in his life. Including from a family perspective, which we find out about. And it's just one of those layers there, which I think in line with the whole film, where you get a sense of something, but it’s not really pursued too strongly.

C&I: Would it be fair to say Travis is seeking a shot at redemption?

Sen: I think unconsciously, yeah. I don’t think he’s a guy who, he’s found a cause and he’s going out to make himself a better man. I just think he’s responding to this situation he’s in, when he’s faced with this Indigenous family who doesn’t want to talk to him, but he does. He’s alienated from his own child. And when he sees the children out there in that town, I think that those children light a spark in him, and make him feel like even though he’s helping those kids in a way, he feels like he may be helping his own in some way.

C&I: What did you have to tell Simon about Travis — and what did you withhold from him?

Sen: [Laughs] We are both a bit ambiguous towards each other actually. He’s got secrets about this character, and so do I. I didn’t really feel the need to tell him too much actually. Once Simon agreed to do the film, we just worked on that character together. And I think I was adding a lot of physical traits, which were signposting Simon to actually head down a certain area. As soon as Simon agreed to do the film, I changed a lot of the stuff in the script about his appearance, just because I wanted Simon to feel quite different in this film compared to his other work. I immediately started to write “buzz cut” and “tattoos,” and just listening to evangelistic radio and all this stuff. And then he’ll take these cues or these messages, and work with that, and he’ll suck it up into his own consciousness.

C&I: Now I must be careful about some of these next questions, because I don’t want to spill any beans. But there are a few points in the film where the audience might expect your conventional tough cop to deal with rowdy locals, and have to punch or shoot himself out of the situation. But you deftly avoid that. Did you ever feel like you were maybe teasing the audience? Like, “Yeah, you’ve seen something like this in other movies, but you’re not going to see it here.”

Sen: I don’t know. I think when you have a story about a cop, there’s inherently a lot of tropes, if you will, that people expect. And for me, it was just about trying to be realistic and subtle and truthful. Because I think in all reality, if you have a police officer coming to investigate a 20-year-old cold case, you’re up against it. And the chances that you're going to have to pull your gun out and go crazy with it is very low. And also, the chances of solving [the mystery] would be almost zero.

I talked to other detectives when I was writing this, and got different perspectives. But I think it just needed to be within the realms of reality, so it connected with the reality of this situation where this indigenous family is stuck within this limbo — because they’ve lost a family member a long time ago and it fractured the family, and they really haven’t recovered.

C&I: It does take a while for Travis to get any member of the family to speak freely with him, much less trust him. He eventually gains the confidence of Emma, the missing young woman’s sister. But, again, the relationship doesn’t turn out the way you would expect in a more conventional movie.

Sen: That’s Natasha Wanganeen [pictured above with Simon Ward], who plays Emma. She’s a local Indigenous girl from that general area. And I just felt like she had a presence that felt right and connected. And whenever possible, I try to find actors, whether they’re small roles or children, who come from the area where the story is set. Like the children in this film, who I think are extraordinary. It’s like I was saying before about how location creates us. We are products of our environment. There’s the land, then the people grow upon that and affect each other. So I think it’s important to try to cast local people from the area where you were from. Natasha has done some work before, but I don't think she’s had a role for quite some time. And she really enjoyed the chance to work with Simon.

C&I: To me, one of the defining bits of dialogue in the film is, “Sometimes you can just never find the truth. You’ve got to find another way to make peace.”

Sen: That’s what a lot of my family and other Indigenous families in Australia have been forced to do. Because we’ve had these murdered Indigenous missing women, and we haven’t had any closure on a lot of the cases. And the peace is rarely found, I think. And then there’s all the substance abuse and all of the social issues that come out of this thing. And this is also connected to this intergenerational trauma that gets passed down through the generations. So in a broader sense, I think it’s something we all deal with in our own personal lives — dealing with some sense of closure if we don’t find the truth of something.

C&I: Again, I’m trying to be as evasive as possible, but I got the impression Travor has done as much as he can to bring peace to these folks. Do you think, as he drives away, he feels any sense of satisfaction?

Sen: I think there must be a sense. But I also think he’s just in this dazed mixture of emotions where there’s a sense of satisfaction, but there’s a sense of loneliness, despair. Maybe there’s something like, this whole situation has encouraged him to reconnect with his own child. I think that it’ll be a whirlpool of emotions, and that’s what I said to Simon when he were playing that scene. I often talk about a whirlpool of emotions, because I think it’s too simplistic to try and narrow it down.