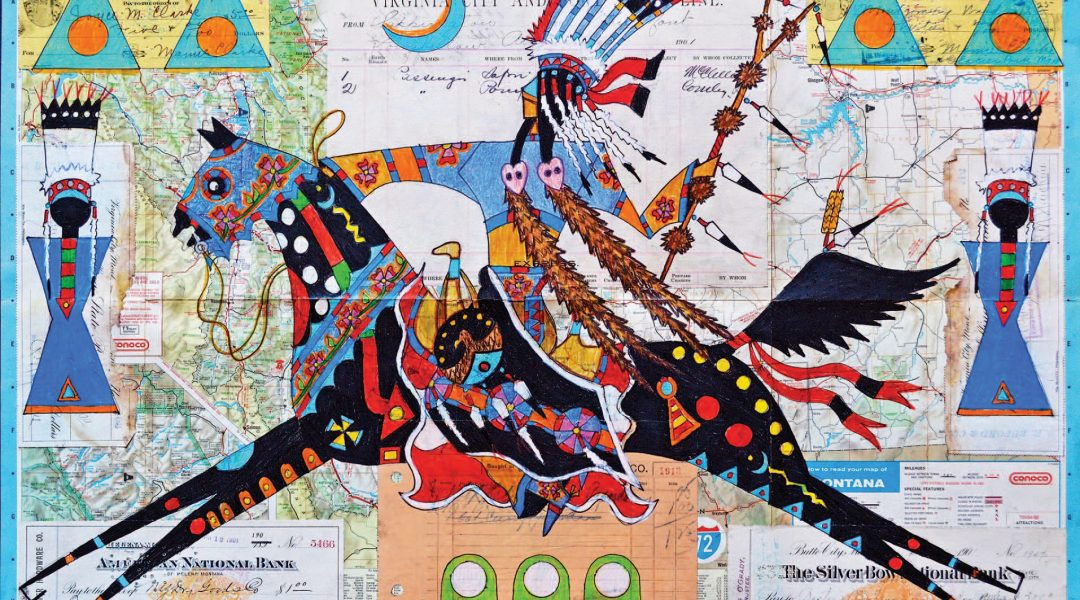

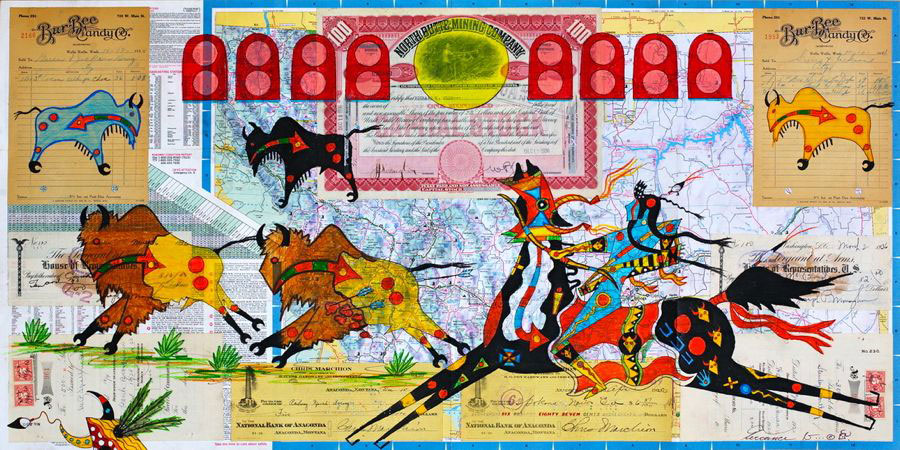

Modern ledger artists explore tribal life by resurrecting a 19th-century art form.

Call it career planning day in Mrs. Horn’s third-grade class at K.W. Bergan Elementary School. It’s the 1970s, and these kids on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Browning, Montana, won’t land in the workforce for some years yet, but Mrs. Horn already wants her students to be thinking about important work they could be doing.

“We were going around the classroom,” says Terrance Guardipee, whose traditional name is Last Gun and whose transferred Indian name is Last Eagle. “You’d stand up and say whatever you wanted to be and everyone was doing the usual: fireman, soldier, doctor. I stood up and said I wanted to be an artist. She said, ‘You have to pick a real job. That’s not a real job.’ I sat down. They came back around again, and I stood up again and said I wanted to be an artist — that was it. She had to let it go, I guess, and moved on.”

There was a teachable moment involved, but not for the student, and not right away. That came slowly, over several decades, as Guardipee and a growing cadre of other artists started conjuring to life the horses and riders and designs of an earlier age by reviving a 19th-century genre called ledger art. It has its name because Plains Indian artists, who had previously painted on hides using paints made from plants and minerals, adapted quickly to putting their art on paper — even lined paper from accounting books that was never intended for drawing.

“Even before hides became scarce, artists began placing pictures on convenient trade materials, such as the bound pages of account ledgers. Nineteenth-century drawings on paper of many types are often called ‘ledger art.’ Pictures on paper and on muslin, which replaced hides for tepee liners and some clothing, were drawn with commercial pens, pencils, crayon, and occasionally watercolor paints,” scholar Candace S. Greene writes in Handbook of North American Indians, Plains.

Especially after dozens of warriors of different tribes were encouraged to draw while imprisoned at Fort Marion, Florida, ledger art became influential for a time in artists’ home communities. Artists preserved culture in drawings that also embodied what scholar Jacki Thompson Rand describes as “subtle forms of resistance that carried Native America into the 20th century.” She sees in those artists’ work the stirrings of a national literature.

But there came a lull in the early 1900s in Plains pictorial art in many tribes. And once Plains Indian art revived in the late 1920s, those leading the way were often academically trained painters who painted as they’d been taught. The naive genius of ledger art was forgotten — for a time, anyway. “By the early 20th century, this art form had all but disappeared,” notes historian and professor of Native American studies Colin G. Calloway.

But it has reappeared in recent decades. Since the late 1990s, an increasing number of American Indian artists have been trying to capture some of the vibrancy of Plains Indian art of the late 1800s by creating modern ledger art. “There’s a lot of ledger artists out there. Twenty years ago, there were probably twenty of us nationally. Now there are probably two to three hundred of them out there because it’s popular,” says Donald Montileaux, an Oglala Lakota ledger artist who has a studio in Rapid City, South Dakota.

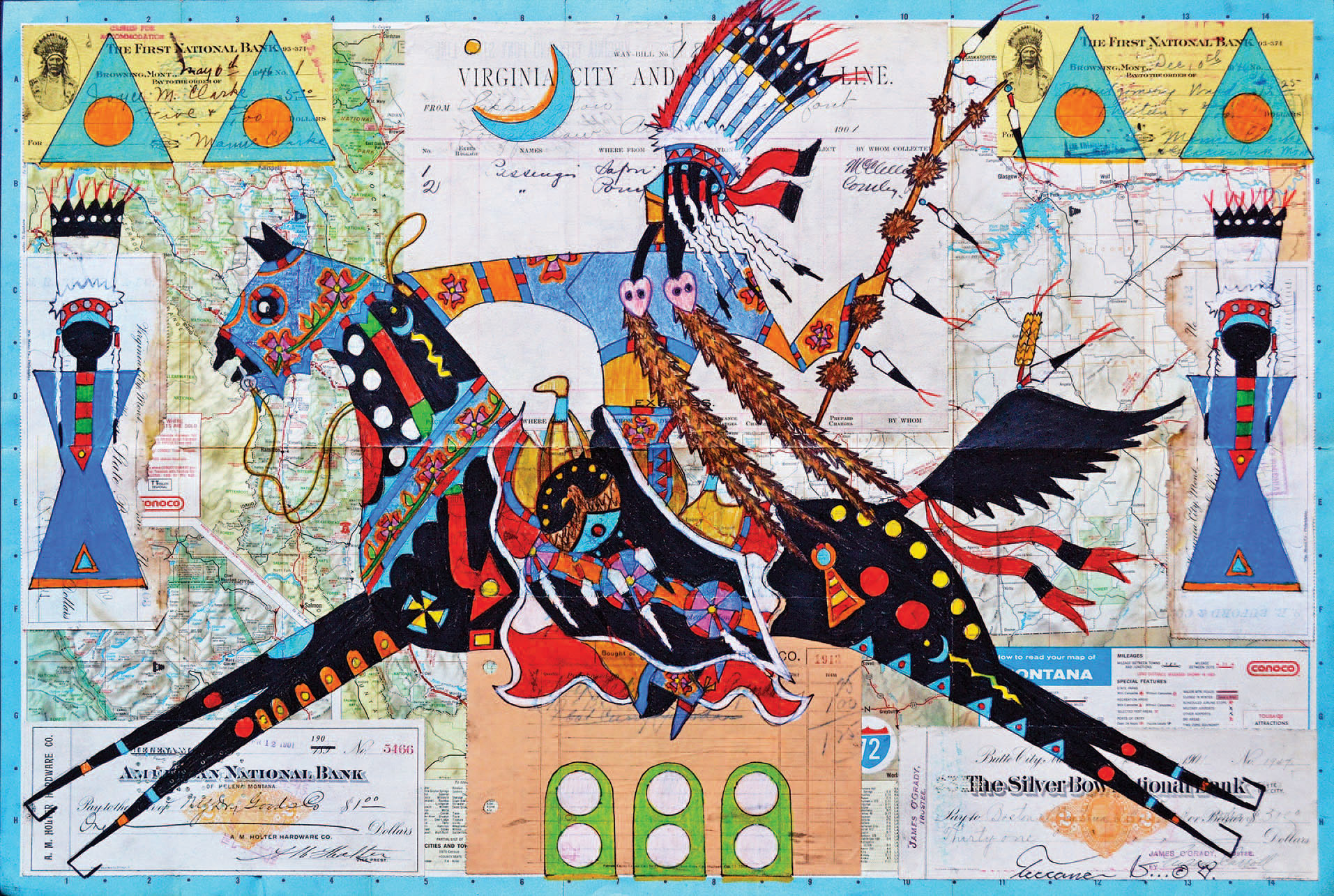

Guardipee, who lives in Issaquah, Washington, but returns often to the mountains and plains of Montana, suspects that some artists get into it simply because it sells well. For him and for many others, though, it’s still a great tool to preserve a tribe’s culture. “It also allows me to bring my ancestors back to life in a modern version of them but still keeping true to the designs and the headdress and the colors and everything like that,” Guardipee says. “I’m happy that the ledger art form came back to life. It’s growing well every year. More and more people are doing it.”

Guardipee is proof that ledger art is leading to other things. “I just did a blanket for Pendleton Woolen Mills,” he says, adding that the blanket features historic Blackfeet figures Mountain Chief — a leader once feared and targeted by the whites — and a woman warrior named Running Eagle. “It’s called Lords of the Plains. It basically looks like a giant ledger, but it’s a woven wool blanket.”

And Mrs. Horn, his old teacher from Browning, Montana, who didn’t think artist was a real job? “After the Smithsonian bought 35 pieces from me, she realized it was a real job. We laughed about it,” Guardipee says. “She was always proud of me, of what I had done with my art and what I am continuing to do.”

The True Story Of The Paper

At the heart of ledger art is an American Indian fascination with paper. And modern ledger has an added aesthetic element that 19th-century ledger artists didn’t have: The material that was simply a contemporary trade article for artists in, say, 1880 is now a historic artifact. Many modern ledger artists choose to use these historic ledgers — paper that’s often a century old or older — as the surface for their drawings. That makes looking at contemporary ledger art a bit like time travel.

“It’s kind of neat to take some of these old documents, because you can look at it in white culture as a snapshot in history — whatever was happening in that grocery store or whatever on that day. Then on top of that, contemporary people are putting an image,” says Dolores Purdy, a ledger artist from the Oklahoma-based Caddo Nation who lives and works in Mesilla, New Mexico, where she has her studio. “It’s kind of fun to add another layer.”

Montileaux looks for authentic ledger books from the period between 1860 and 1920 — and has found all the ledgers he needs with the help of a business trick. If someone gives him a ledger, he’ll give back a piece of his art drawn on one of its pages. Like other ledger artists, he doesn’t mind if pages are written on. The writing often adds value because of the history it carries.

“All my pages that I draw are from real books from that period. There’s no copies or anything like that. They are the original pages,” Montileaux says. “It’s like a day of life: I got tobacco today, I got coffee, I got some eggs. Or they were loading a wagon to go up into the Dakota Territory and had blankets, barrels of sugar, flour. Most of the books that I have are of what’s being loaded off the railroad and into a store, a trading post, onto freight wagons and those freight wagons are going out into who knows where.

“I get some ledgers, and they’re beautiful. They’re leather-bound, and the paper quality is just unbelievable. They’re all watermarked, and the writing in them is extraordinarily beautiful because each G, each A throughout that whole book is consistently the same. I sit there and think, It was 1876, and he or she was sitting down — probably a he — was sitting down with this book and he was writing information. What type of home did he have, what was his culture? He’s out here in Chadron, Nebraska, and he’s probably from New York or maybe he’s even from London, England, way out here. How long did it take him to get here? All those things go through my head.

“The other thing that goes through my head is, This is so beautiful — how can I take a page out of this? But then the rent comes due or I get hungry or something like that. That overpowers the desire to keep the book intact.”

For Guardipee, who acquires ledger books and other historic documents from Montana for his art, paper carries the same fascination. He notes that paper hasn’t always been an honest article in the history of the American West. Putting a ledger book in the hands of an artist gives paper a chance to turn over a new leaf.

“Paper, I think, is a very powerful thing — the way we use it and the way it was used against us, and the way I’m using it now to express myself as a Blackfeet and show the outside world the beauty and the power of my tribe,” Guardipee says. “I want to express our culture by using that paper that was at one time basically an enemy of ours. It was used against us with these different treaties, with words written down on it that made promises to us. This way, I’m making promises to the world with my art but it’s through my culture — they can experience that. All the things I’m putting on the paper are true. There are no lies. The people are all people who walked on the earth and the designs are all used to this day.”

Drawing In Present Tense

Montileaux, who is famous among colleagues for drawing horses that seem to fly off the page, believes it’s good that ledger art is becoming more diverse, with artists drawing more than warriors on horseback. He’s fascinated by the work of an Oglala Lakota colleague, Dwayne “Chuck” Wilcox, who also lives and works in Rapid City, South Dakota.

“He’s a ledger artist but he does things differently than I do,” Montileaux says. “He has a real cool slant on humor. He uses traditional way of dress, but with an iPod stuck in there someplace, or a computer.”

Odd as it may seem for art buyers who want to see ledger art depicting Plains warriors on horseback, Montileaux suggests that Wilcox’s choice of subjects — the Indian with the computer and the like — might actually be true to ledger art’s beginnings. “Ledger art was always what was happening at the time. Those guys who were doing ledger art 150 years ago were doing what they lived — that’s what they were recording. They weren’t trying to do 150 years ago. They were the camera of that age, that time period.”

American Indian students at Eastern boarding schools created ledger art, often with a little nudge to depict Plains culture as whites imagined it. “That’s why the boarding schools encouraged Native people to do ledger work. They wanted them to do pretty horses and things that were 20, 30 years prior. But those guys who were institutionalized, they were doing things that they had seen because they wanted to take those things back to their people on the reservations and say, ‘Look at this, man, this is what they call a boat. This is how many people there were in the city.’ ”

Wilcox began to note the possibilities of ledger art when seeing one particular picture. “There was one artist who really put me over the edge and that was Amos Bad Heart Bull,” he says. “Later in his life, he drew a ledger drawing. This was the one drawing that really moved it forward for me. He did a piece of himself at his cattle ranch.”

It wasn’t astonishing in itself, but it showed that the American Indian in the picture had made the transition to cattle rancher — not a bison hunter, but a rancher, with cattle, horse, boots, spurs, chaps, and Western saddle.

“I looked at that and that was the epiphany for me — that we didn’t really move forward with this, and that our stories today were still struggling with some of the same issues we had then. I didn’t see anybody doing really contemporary or political imagery,” Wilcox says. “That’s where I found a hole in the clouds, I guess.”

The revelation made Wilcox realize that the way to maintain the traditional concept of ledger art without having it become static was to move it into his own time frame. Oddly, for an artist whose work is regarded for humor, Wilcox believes ledger art shouldn’t shy away from dealing with topics that are deadly serious and that don’t necessarily appeal to collectors. “Nobody’s going to frame that and put it on the wall — alcohol and drugs and things like that, real contemporary issues that we still have.” But, he says, ledger art remains relevant precisely by confronting such issues.

“If you go to any of our gatherings, you’ll see young people on their phones or taking selfies and all this other stuff. That’s something that’s really contemporary,” Wilcox says. “I’d like to see this art format move forward into the future. I don’t want to see, 500 years from now, our young people or artists from our culture still drawing a warrior on a horse.”

Still, there’s definitely room for art that celebrates the golden age of Plains Indian culture. “Don [Montileaux] really does an eloquent job of such a thing, and it’s really contemporary, the way he does that.” But, Wilcox maintains, ledger artists also need to look at their own times and their own peoples and put down on paper how the tribes are living now.

That’s why Wilcox — connected to a Lakota tradition that celebrated a major victory over Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer in 1876 with pictures of horses in battle — drew ledger art of a different kind of warfare 125 years later: It’s a picture of himself and his daughter, sitting in their living room watching the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on television on September 11, 2001.

A Woman’s Touch For A Man’s World

In the introduction to their guide to ledger art in American collections, scholars John R. Lovett Jr. and Donald L. DeWitt note that artists in the first great age of ledger art drew such subject matter as village and social life, ceremonies, hunting, catching of horses, and individual battle exploits. With such themes, it’s no surprise that 19th-century ledger art was largely a male pursuit, emphasizing what researcher Joyce M. Szabo aptly calls “the warrior tradition of exploit painting.”

“Generally this was considered to be warrior art and generally it was drawn by the men — they were the warriors,” Purdy says. “But there were some female warriors, women warriors, and they were also known to have done some ledger work.”

But that was already changing in ledger art of the early reservation era, as battles and horse raids declined as subject material, while activities such as courting or domestic life appeared more often. Modern ledger art is not only freer about subject matter, but also about the artists who are practitioners. Nowadays, Purdy says, most new ledger artists welcome female colleagues, and late 20th- and early 21st-century ledger art might as easily focus on women actors.

“Women just bring a different perspective to ledger art, just like today you find men who are potters and beaders,” she says. “They are readily accepted by the women because they bring a whole different look into some of the beadwork. Women bring ... one perspective into a male-dominated art, while males are bringing a new perspective into female-dominated art.”

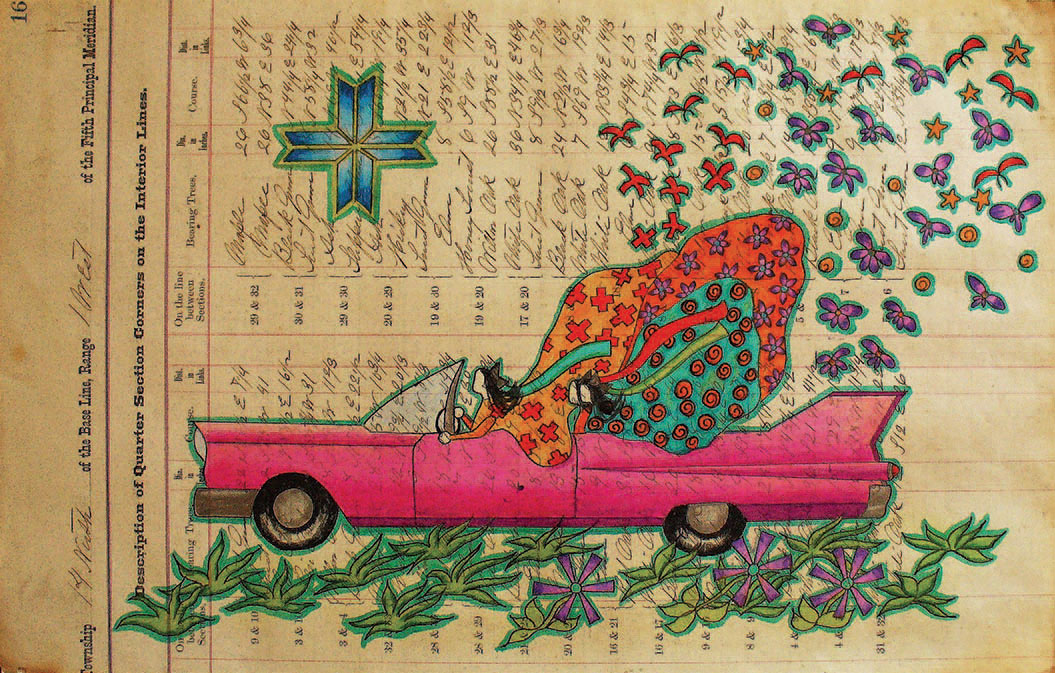

Purdy is well-aware of the possibilities for showing the female side of life in Indian Country, whether that’s a picture of women strolling about with parasols — she’s open about her appreciation for Japanese art — or joyriding in an automobile.

“Humor and bright colors are an important aspect in some of my work. I have a series of Caddo-lac women, which I spell C-a-d-d-o-l-a-c. The women are in 1959 Cadillacs,” Purdy says.

There’s also room in modern ledger art for looking back on women in tribal histories. One of Guardipee’s favorite subjects is Running Eagle, who is one of two historical Blackfeet figures featured on the blanket he did for Pendleton Woolen Mills. He has drawn her time and again.

“Running Eagle was a member of the Crazy Dog Society that was traditionally an all-male war society. She lived in the mid-1700s to probably early 1800s, I’m guessing,” Guardipee says. “In Glacier National Park there’s a waterfall named after her called Running Eagle Falls. She was a Blackfeet woman warrior, one of the only ones. When you see my work, you’ll see the woman warrior on many images I’m doing. You’ll see a woman riding sidesaddle, even though she didn’t. She’s in a dress. I’m showing femininity.”

Revising Old Ledger Accounts

Old and versatile though it may be, even ledger paper finds it difficult to account for old wrongs.

Wilcox makes a point of making fun of Indian fighter Custer because he thinks mainstream culture has idolized him too much. “He was such a martyred person. In Montana they have Custer Gallatin National Forest and down here [in South Dakota] we have Custer State Park and Custer, the town. They’re really adamant that Custer was a really good guy when the history basically says no, he was kind of a bastard. So I do make a kind of contemporary line of that. I do an ongoing, open-ended thing I call ‘leveling the playing field,’ ” Wilcox says.

Atrocities in Western history, though, are hard to deal with, even more than 100 years later. For Montileaux, the experience of Wounded Knee — the December 29, 1890, massacre in which some 250 to 300 Lakota Sioux men, women, and children were killed — is too painful for him to broach in his art except in rare instances.

“There are only two pieces I’ve done about Wounded Knee. Those were hard, hard pieces to do. That hurts. I would rather do a warrior flying down the hills with his finery on. You’ll notice there’s never anybody that’s on the other side that’s taking the brunt of the attack in my pieces. There’s never somebody dying in my pieces.”

Guardipee finds it similarly difficult to deal with the massacre of January 23, 1870, in which troops of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry under the command of Maj. Eugene Baker destroyed a peaceful Piegan, or Blackfeet, village on the Marias River. Although they were looking for the village of a man named Mountain Chief, the federal troops attacked the camp of Heavy Runner instead. Some estimate that about 200 men, women, and children died in what whites sometimes call the Baker Massacre.

“We call it Bear River Massacre,” Guardipee says. “We don’t mention Baker anymore because of the situation that happened. Most of us would rather not say his name.”

The Bear River Massacre cuts close to the bone for Guardipee because Heavy Runner was his great-great-grandfather. A son of Heavy Runner named Last Gun escaped. Last Gun’s son, Many Bear Heads, was Guardipee’s grandfather.

“I haven’t done any imagery on Heavy Runner or on Bear River Massacre because I look at that as very personal. I never really thought of doing any imagery on it. I might one day before I go to the next world.”

If and when Guardipee is able to do such a picture, ledger art, he says, would be a good vehicle for saying what must be said. “The past is the past, and sometimes it wasn’t a very lovely past. It’s the truth. It’s just how it goes.”

Learn more about the artists on their websites: terranceguardipee.com, donaldfmontileaux.com, doghatstudio.com (Dwayne Wilcox), dolorespurdy.com.