In the exhibition As We See It, contemporary Native American photographers portray a gamut of subjects with a common underlying theme: the vitality and perseverance of their people and cultures.

The nostalgic images of late 19th- and early 20th-century photographers such as William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Edward S. Curtis created an impression of an indigenous culture receding into the past. But the prevailing view of the time that Native Americans were vanishing proved fallacious.

“The works those early photographers left influenced both the general public and the government, validating the efforts to remove Native people from their lands,” says Suzanne Fricke, co-curator of the exhibition As We See It: Contemporary Native American Photographers. “As a counter to these older representations, the artists in this show offer complex perspectives on contemporary life, creating new images to replace the older stereotypes.”

On view through May 13 at the New Mexico State University Art Gallery in Las Cruces followed by a fall exhibition at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, As We See It is a collection of works by 10 contemporary Native American photographers and filmmakers that “captures a range of responses to contemporary life,” Fricke says. Whether it’s examining the role of the individual within a tribe, exploring concerns about the environment, or reframing of the past in the present, these photographers are using contemporary art and photography as a vessel to reverse the belief that they are “vanishing people.”

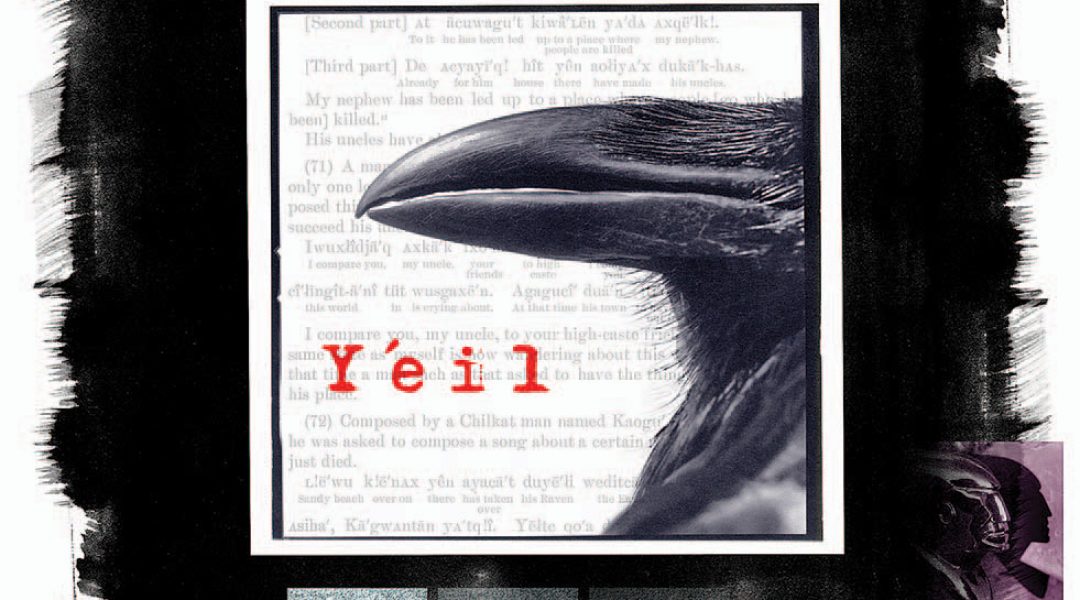

Larry McNeil

Tlingit | Boise, Idaho

Larry McNeil has used the character of a raven throughout his works for nearly 20 years and describes the protagonist “trickster” as a way to make people laugh when addressing controversial topics in his photographs. A professor of photography at Boise State University, McNeil uses his images to probe topics such as the misappropriation of Native American symbols, stereotyping, and climate change.

From satirical dialogue between a bird and a car hood ornament in Raven Asks Pontiac to naming glacial ice as the “new endangered species” in Global Climate Change (included in As We See It), McNeil’s witty tricksterlike tendencies help to approach important issues in a strategic yet endearing way. As an example, Fricke points to his series Tonto and Lone Ranger Escapades: “Larry digitally adds images of the Lone Ranger behind bars and Tonto making his escape in a bright green Cadillac, a wry commentary on Tonto’s legacy in film and television.”

He won the All Roads Indigenous Photography Award from the National Geographic Society in 2006 and has exhibited work in a number of prestigious museums around the world, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of Scotland.

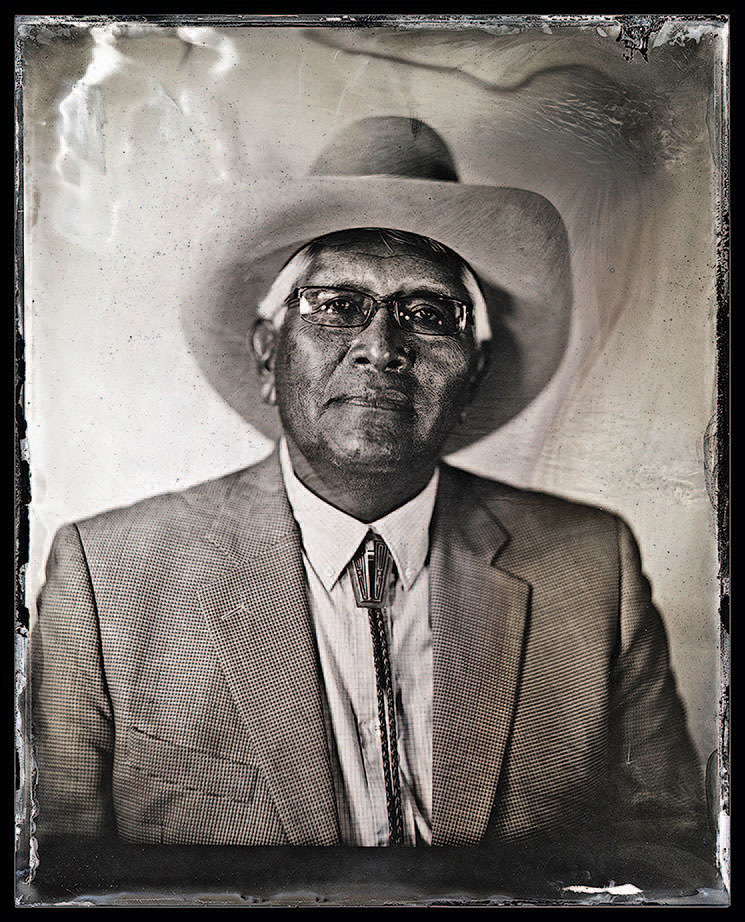

Will Wilson

Diné | Santa Fe

Will Wilson hopes that people see a new and exciting vision of what photography can be from his perspective as a 21st-century “cultural practitioner.” Inspired by the post-apocalyptic films The Omega Man and Planet of the Apes, Wilson investigates environmental degradation as well as indigenous populations’ responses to catastrophe in his project Auto Immune Response (on view recently at Peters Projects in Santa Fe). The series of photographs puts a solitary Native American man against an empty reservation backdrop and addresses the transformation of indigenous life with focuses on botany and food systems.

The tag line of what is perhaps his largest project, Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (included in As We See It), poses the insightful question “What if Indians invented photography?” In this body of work, Fricke explains, Wilson reverses the usual portrait method in which a photographer takes an image while the sitter remains passive. Instead, he asks for volunteers and takes a tintype portrait. Wilson then gives the tintype to the sitter, and the sitter gives the artist digital rights to the image. “By using an older technique, Wilson addresses the importance of the history of portraiture to Native American cultures,” Fricke says. “And by sharing the process, he creates a more collaborative practice.”

According to Wilson, reciprocal magic is generated when people come together to make a portrait. “It’s about the relational aesthetics that flow from the engagement,” he says. “The photographs are secondary.”

Some of Wilson’s work is a direct response to, or in dialogue with, Curtis’. For the exhibition PHOTO/SYNTHESIS (on view through April 2 at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman, Oklahoma), he shot descendants of some of Curtis’ original subjects. Wilson’s contemporary portraits are paired with Curtis’ historic images, giving lie to the misguided 19th-century notion of the vanishing “noble savage.”

Shelley Niro

Mohawk | Brantford, Ontario

Artist Shelley Niro uses film, painting, sculpture, beadwork, multimedia arts, and still photography to craft powerful narratives that are sometimes humorous and other times solemn. Niro incorporates familiar pop culture elements, such as Marilyn Monroe references in The 500 Year Itch, to address pressing issues without jeopardizing the history and integrity of her culture.

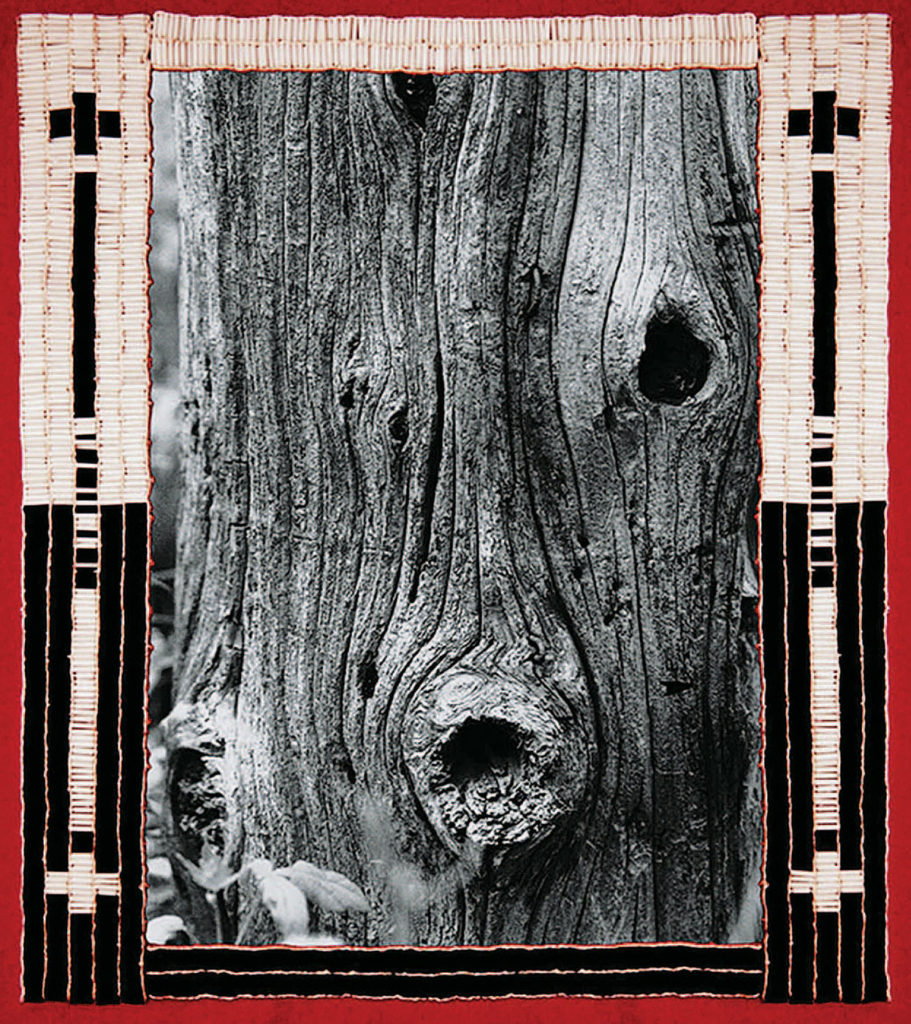

“Her series Pieta, selections seen in As We See It, uses images of wampum belts to frame the landscapes, which represent lands that were lost through war and destruction,” Fricke says. “Wampum belts represent important treaties between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the United States government, promising peace and autonomy. The title refers to Michelangelo’s famous St. Peter’s Basilica’s Pietà, [which depicts] a mother holding her dead son, aware of her loss but holding her grief at bay. By combining the promise of peace with harsh reality, Niro shares her personal view, a maternal perspective on loss.”

Niro received her master of fine arts from the University of Western Ontario (now known as Western University) and has displayed works at the Canada Council Art Bank, Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, Canadian Museum of History, and dozens more. Her award-winning films have been screened numerous times at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian as well as at festivals worldwide.

Tom Jones

Ho-Chunk | Madison, Wisconsin

From representing the Ho-Chunk Nation through portraiture in Strong Unrelenting Spirits to shedding light on the “post-Indian” issue of artists minimizing or denying their heritage in I Am an Indian First and an Artist Second, Tom Jones’ photography addresses critical issues surrounding Native American culture. In keeping with his unconventional and abstract approach, one of his most recent projects, The North American Landscape (selections from which are included in As We See It), examines the role that toys have in teaching children about history. A play on the title of Curtis’ The North American Indian, this series of photographs features small toy trees that represent different landscapes from areas where American Indians reside.

“Tom Jones uses photography as a tool to reexamine the historical and current representation of American Indian culture,” says Sherry Leedy, director of Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri. “He is interested in assessing how non-Natives use the identity and landscape of Native people today as material objects, architecture, and advertising.”

Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art has hosted a number of Jones’ one-person shows and recently mounted Back Where They Came From, which Leedy and Jones curated together. The show featured the work of 19 contemporary Native American artists with the goal, Leedy says, of “locating contemporary Native American art in the larger contemporary art world context.”

As for where Jones’ work resides in that context, it’s through the lens with a modern mind-set but a strong connection to his parentage. His passion for photography began long before he was hired on as assistant professor of photography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Photography has always been a part of my life,” he says. “It came to me through legacy. My father, upon returning from World War II, attended Yale on the GI Bill to learn photography. He went on to be a photographer and work in the photo-finishing business his whole life. For many years, he was a district manager for Kodak, so cameras were always in the house.”

From the April 2017 issue.